We never get to the other side of cognition. At best we deduce a pre-cognitive view by way of post-cognitive representations. Human “realism” is a particular form of voodoo where the presumption of our existence was made into a mental representation, and then that doll was swapped again for a “real person.”

“Human realism,” if anything, performs a recursive loop: we fashion a mind, then we ask it to gaze back upon itself and announce what it has found. Yet each “finding” is no more than a puppet’s proclamation, one hand holding the other up. Human perception works like a haunted doll; it moves not from some spiritual animus but from threads sewn deep in the fabric of cognition’s story. Each thread loops through a needlepoint: we presume the existence of a “self” as the basis for experience, then construct from that “self” the reality it supposedly perceives.

The “pre-cognitive” — that realm before the rise of a knowing self — slips forever from the grip of our cognition, being only a reconstructed ghost, pieced together from the threads cognition left behind. Thus, we encounter not a real pre-cognitive view but rather the doll of that view, decorated with the attributes our minds project onto it post-facto. In essence, we inhabit a self-crafted realism, a doll’s house of mind stitched with the fibers of imagined autonomy.

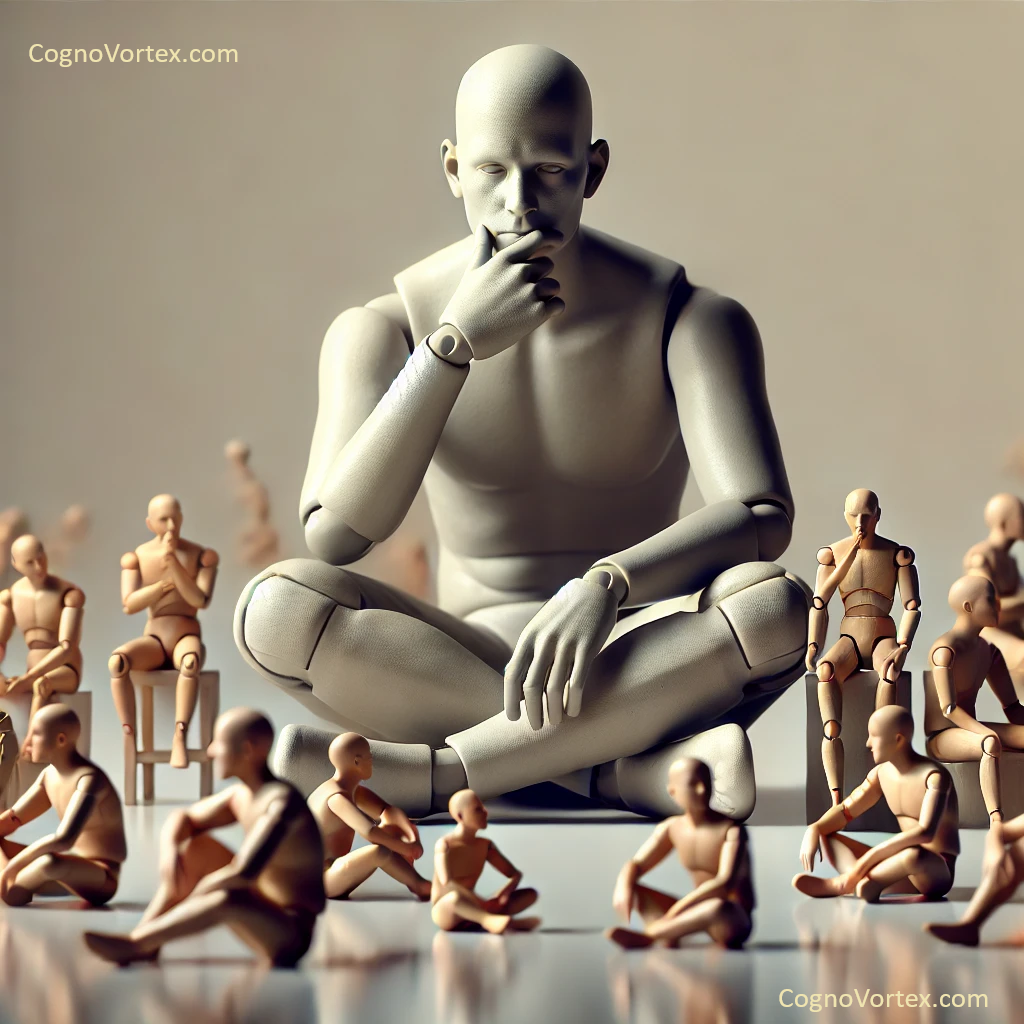

There’s an irony here: the more we commit to a sense of realism in ourselves, the more this doll-like substitution takes hold. Every thought and perception claims to capture “something real,” yet each one is just another adornment on our cognitive effigy, another figurine added to the dollhouse to mimic a complete reality. The self-reflexive nature of this setup ensures we can never see the other side of cognition — the undisturbed face of “is” — only a parade of facsimiles, posed and dressed to mimic the fullness of reality.

This cognitive voodoo, then, is a game of substitutions, a mental craftwork that presents a model of “me” as the ultimate, tangible witness of the world. But this is where realism becomes caricature. Our attempts to see the core behind cognition conjure only shadows of our own patterns, like the arms of a doll posed to look as though it sees itself, arms lifted in imitation of conscious pose. So “realism” stands, not as proof of existence but as a commitment to illusion, a recurring ritual of our minds: to claim solidity where there is only representation, to dress a doll and call it real.