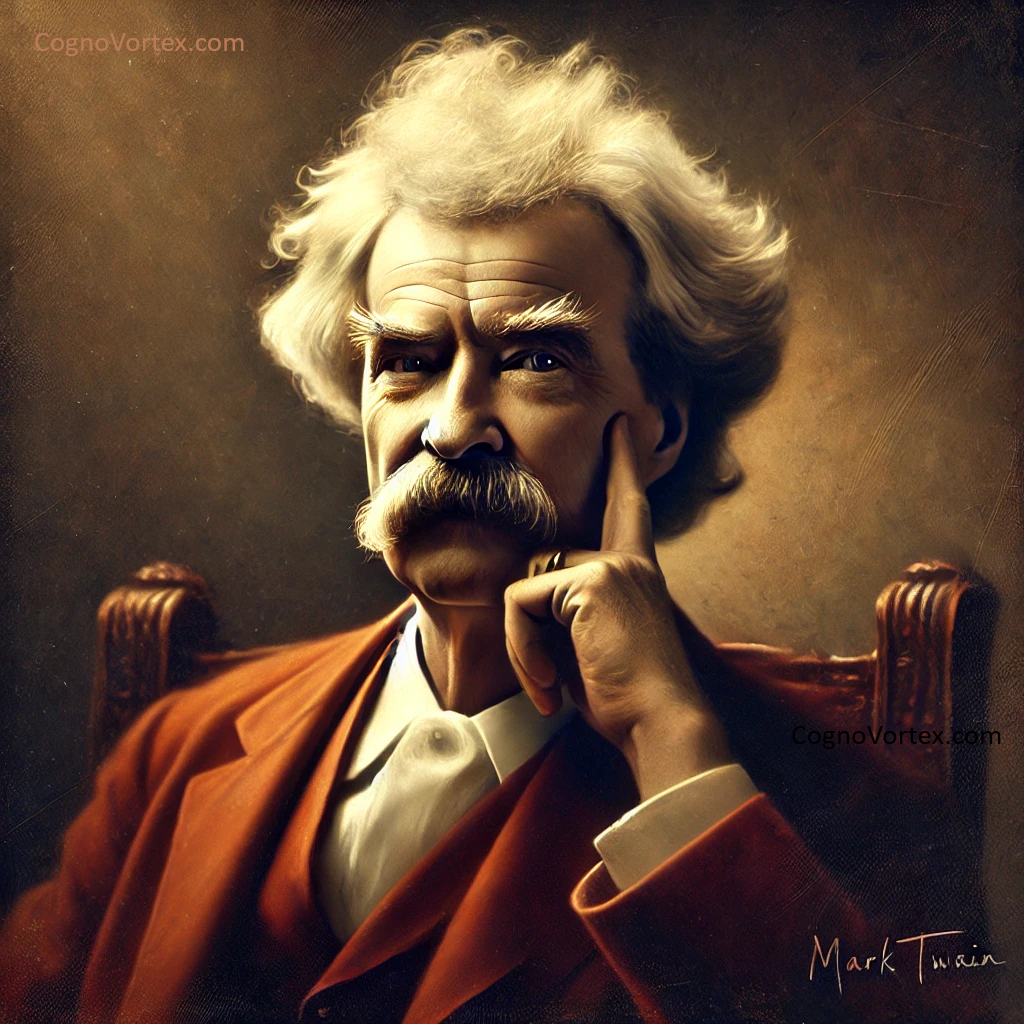

“It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.” — Mark Twain

Mark Twain, with characteristic wit, slices into out confidence—of our tendency to cling most fiercely to what’s most fragile: false certainty. This quote echoes through the lens of perception and pretense, unraveling the often-unnoticed machinery of our belief systems. Certainty, that smooth and opaque surface, feigns solidity while hiding its cracks. But what Twain gestures toward is not merely an error of knowledge; it’s an error of self-reflection, where the perceiver never suspects that their vision is bent. We come to perceive, not truth, but the satisfaction of a comforting fiction—comforting, not in its depth, but in its ease. To “know for sure” is not only a possession of belief but a possession by it, where what is clung to as truth dictates the very terms of perception, until we cease to see the illusion at all.

The “trap” here is not the blindness to something we have not yet learned, but the blindness we ourselves have crafted by overlooking our capacity for error. Thus, it is the strength of belief in what “just ain’t so” that renders our sense of clarity a kind of self-enforced twilight. Our perceptions march forward, content within the limits of their own construction, perceiving ever less in their certainty. The paradox, then, is that certainty blinds by appearing as illumination, not because it blocks sight, but because it denies that there’s anything unseen in the first place. Ignorance, veiled in confidence, preserves itself by casting out all whispers of doubt.

In this way, Twain illustrates the most cunning barrier to enlightenment—not the daunting unknowns, but the comfortable fictions. Ignorance cloaked in confidence operates with a peculiar ferocity: it doesn’t hide in the dark but rather masquerades in the bright, dazzling assurance of being “right.” It is this presumed clarity that turns perception into a mirror that flatters, a mechanism that demands conformity from everything it perceives, so that nothing, ultimately, is seen for what it is. Twain points out that there’s more machinery at work here than any amount of genuine ignorance alone could muster—there is, in fact, a formidable complexity behind the production of our beliefs, where what we assume to be transparent is, in truth, impenetrable.

Mark Twain, with this single line, hands us a caution: to see through certainty and recognize the strangeness of our own knowing. We find the most solid of truths becomes pliable when our own perception is involved, a self-contained illusion that guards its own existence. To confront that illusion, then, isn’t just to learn more or even to unlearn—it is to risk dismantling the entire framework of how we know, leaving us with the far humbler task of perceiving.