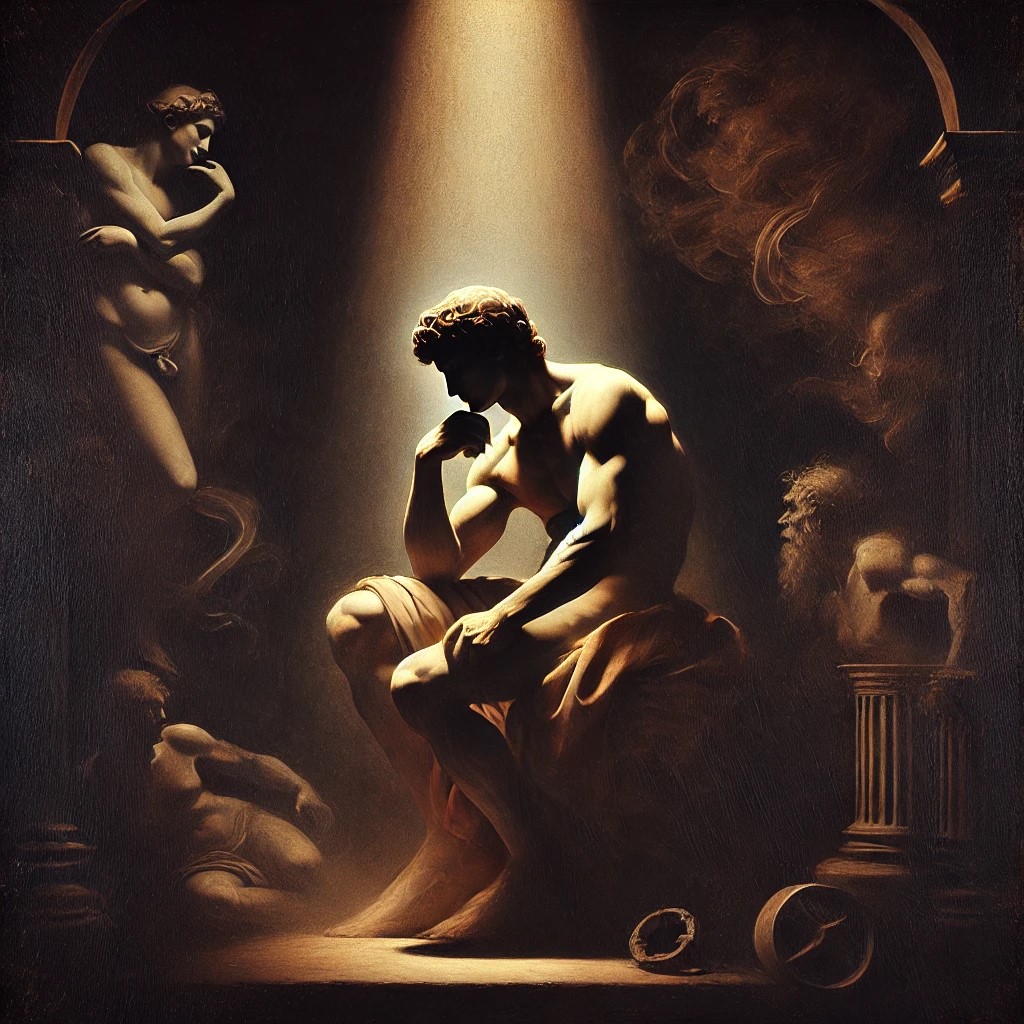

The body’s pains, like its pleasures, often occupy a less conspicuous role than they deserve—as ghostly premises behind our choices, intentions, and delays. Think of “premise” here as the invisible rationale shaping our behavior, a premise not consciously stated, yet persistently present. Pain, especially, operates as a directive, creating a baseline context for action and inaction that rarely enters explicit thought. It is both a condition and a command, but one we rarely acknowledge as such.

The paradox lies in how pain can rule over us while remaining out of sight. Instead of announcing itself as “reason enough,” pain frequently sidesteps such clarity, masquerading as other causes: fatigue, hesitation, “just not today.” It remains hidden not because we cannot see it, but because we do not allow ourselves to see it. We defer to it instinctively, securing permission to avoid constraints by dressing it up in less concrete terms. Physical discomfort becomes, by stealth, a powerful determiner of action—an unspoken “first premise” that justifies delay or nonaction, cloaking itself behind other, more palatable explanations.

In fact, as long as the source of pain lies unresolved, it shapes our actions quietly but thoroughly. The premise can take on an impressive range of disguises: a fatigue toward effort, a reluctance to overexert, even a sudden diligence in unrelated tasks. Whether aware of discomfort or not, we act according to its demands—spurred to escape it or lulled by its silence.

This “hidden premise” then becomes a permission structure—an underground rationale for rearranging our lives around what we rarely name outright. That muscular ache might encourage more frequent breaks, less strenuous activities, an adjustment to priorities. In essence, pain and pleasure set the perimeter of possibility.

Understanding pain and pleasure as such hidden premises reveals their cunning, yet also their power. To recognize them outright allows us, paradoxically, to free ourselves slightly from their grip—not by dismissing them, but by acknowledging them as forces of influence rather than background noise. What we can’t see correctly, we can’t navigate successfully, and so by recognizing these forces, we open up the possibility of deliberate action. With that acknowledgment comes a curious freedom: to choose actions not merely in avoidance or indulgence, but in alignment with intentions we can openly claim.