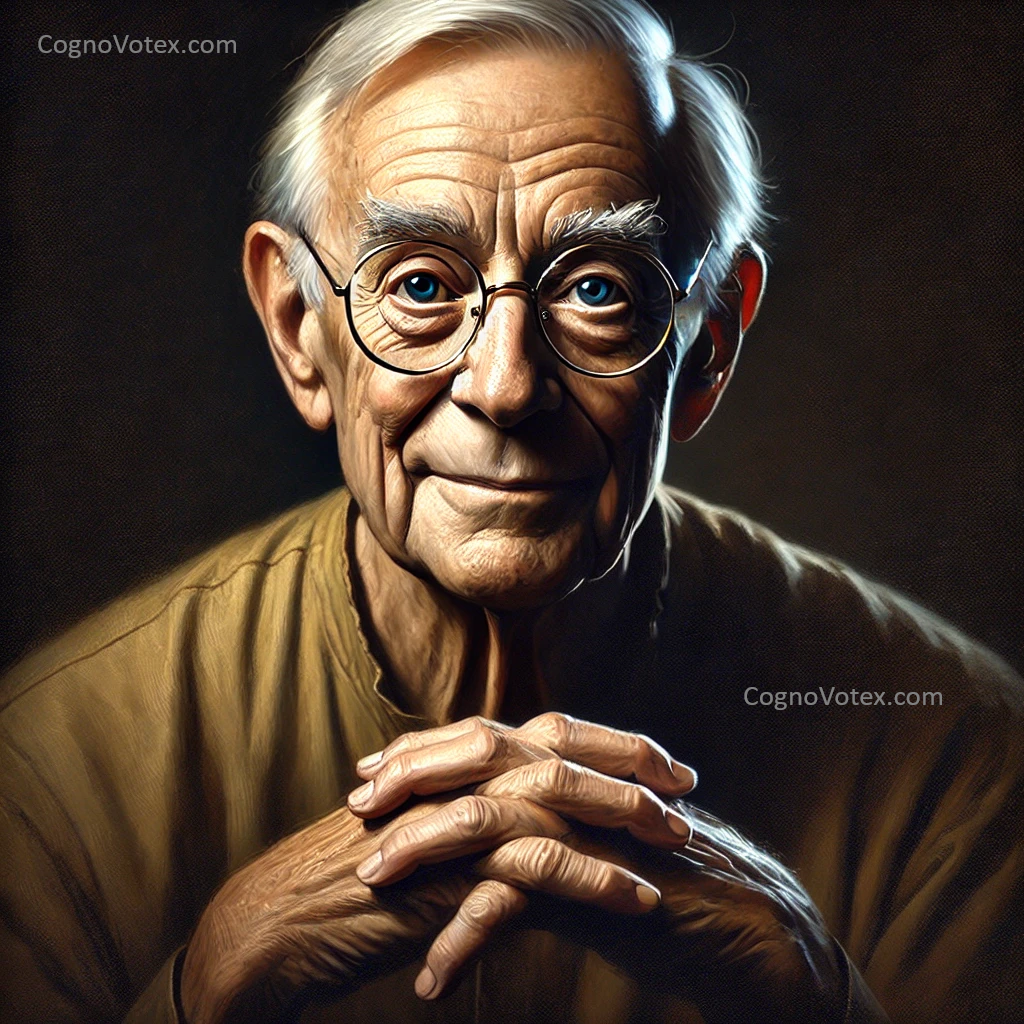

“The curious paradox is that when I accept myself just as I am, then I can change.” — Carl Rogers

In the wisdom of Rogers lies a sly contradiction. Wanting change, as if to cast away some aspect of ourselves, is invariably seasoned with the distaste for what currently is. To want a difference in ourselves—to morph from what is known, even if only half-understood, to the mirage of what might be—betrays a latent rejection, a background of dissatisfaction that threads itself through the tapestry of our desires.

Yet consider: if wanting change often signals a fracture in our own acceptance, then what if the change we sought was the change in our very wanting? What if we entertained the notion that change without self-repudiation exists, emerging not from a position of rejection but from one of affirmation? Accepting ourselves in full could indeed yield a curious change—a shift whose aim is not the eradication of the self but the growth of it, not born of self-discontent but from the act of self-alignment with fate.

This alteration, let’s note, doesn’t promise safety or immunity from vulnerability. It suggests something audacious: a change that rises without the poisonous prick of self-loathing, a change formed not by the hammer of dissatisfaction but by the sculptor’s gentle hand of self-acceptance. When we seek to rid ourselves of what we hate, we declare war against our own nature. But to seek new forms out of what we love? That offers a strange and rare freedom.

If loving the fate of our own wants seems a risk, it’s one worth the dare. Because while the certainty of discontent is easy—insisting upon change, never finding contentment with it—the adventure of genuine acceptance lays a path of constant surprise. For in this acceptance, self-compassion transmutes want into will, and the self evolves not by rejecting its own soil but by growing roots deep within it.