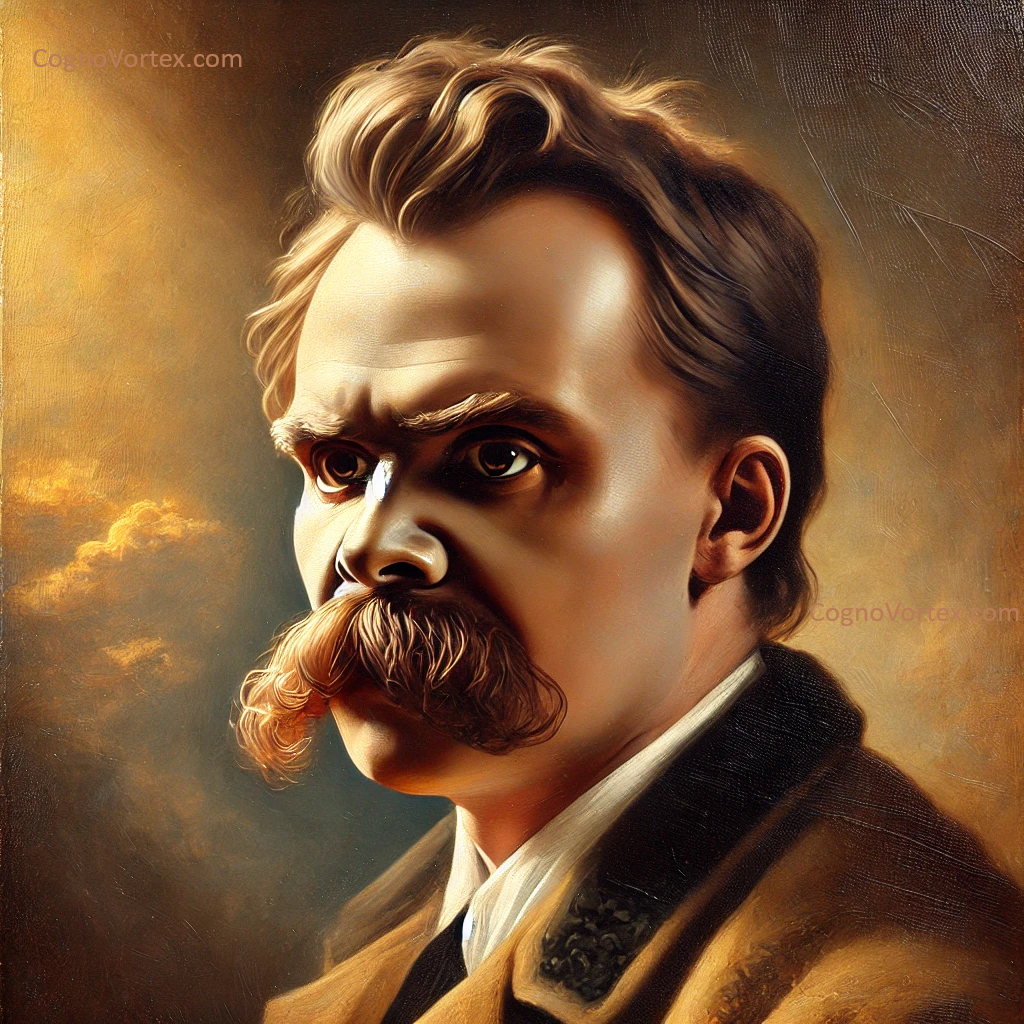

“He who fights with monsters should look to it that he himself does not become a monster. And if you gaze long enough into an abyss, the abyss will gaze back into you.” — Friedrich Nietzsche

To wrestle with a monster is to engage with more than the monster; it is to engage with the mechanisms that produce monstrosity in the first place. Nietzsche’s warning unfolds in layers: at first, it cautions the warrior not merely to face the monstrous, but to scrutinize the act of facing—the reflexive feedback loop that binds action to consequence and actor to action, subtly or swiftly redrawing the contours of one’s own character.

Yet in any act of facing, something eerie happens: the behaviors that initially respond to or repel the monstrous may be counter-monster only in a structural sense. While they act as repellants or mirrors to the monster, they cannot in a true sense reject what created the monster in the first place. This inversion only reflects the original shadow back on itself—actions wear the familiar masks of their antitheses, but do not transcend them. The warrior becomes locked into the very image he opposes, not through some moral failure, but because the machinery of his own behavior has been distorted by fixation. The abyss, then, is no external chasm but the mechanism of gaze itself, an inward drag toward self-objectification.

The philosopher’s abyss does not merely stare back as an empty void but as a projector of behavioral reflexes, rhythms, feedbacks. It responds, reconfigures, and reshapes the gazer’s neural architecture, rewiring perception until the person and the monster are reflections in an elaborate behavioral parody. The gaze into the abyss becomes the unintentional act of reification: in his refusal to become monstrous, the warrior effectively enacts the monstrous.

The term “antimonster” is not truly antithetical but ironic—a reflex that leads to becoming a different variation of the monster, rather than its opposite. True transcendence requires becoming ‘more than monstrous’—an Übermensch, not simply a reaction. Nietzsche’s wisdom here becomes prescient: to face the monster in any true sense requires more than an oppositional reflex. It requires something far subtler—a detachment that does not confront to correct but observes to understand the foundations beneath reflex and response, beyond the abyss and the gaze.

In the end, the monster is not the problem; the gaze itself is the trap.