“There is more ape in man to deny the relation than there is more than ape with which to accept it.”

— Matt Berry

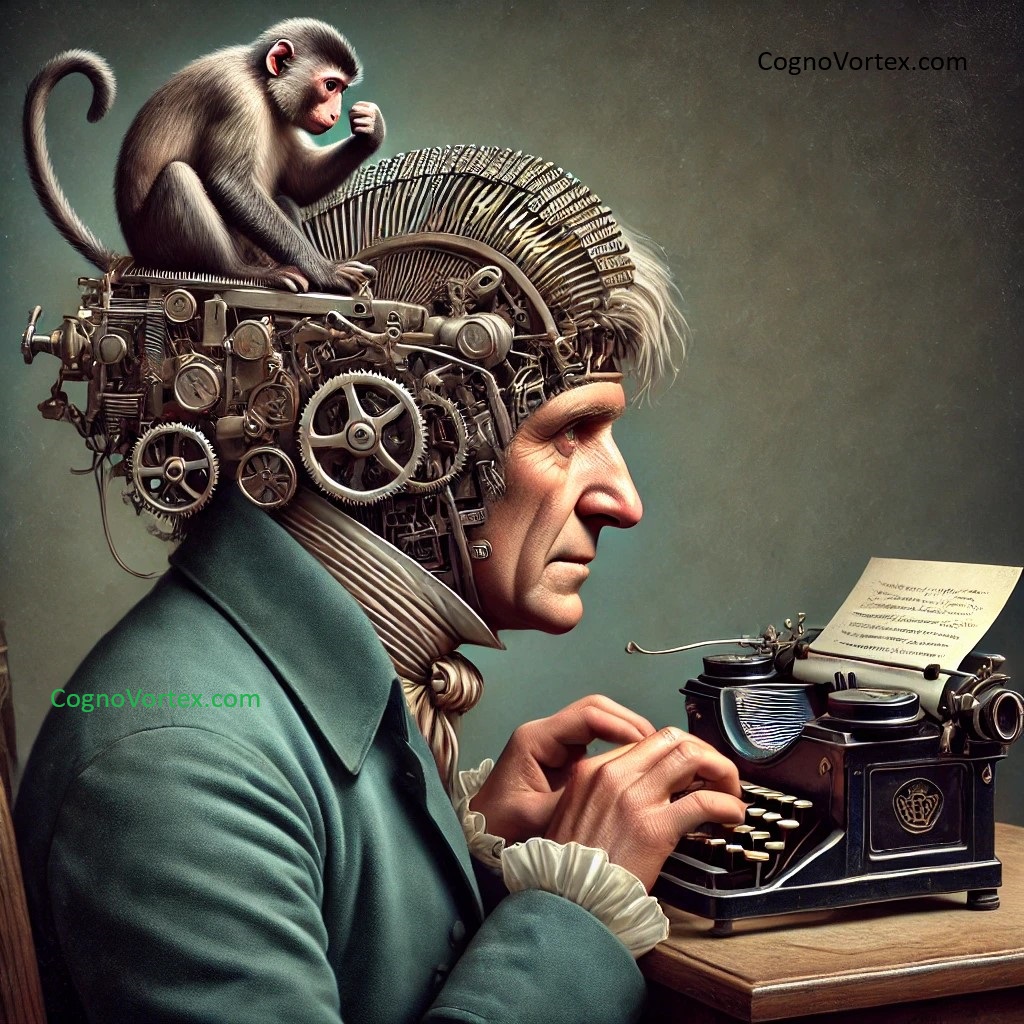

In Nietzsche’s conception of the Übermensch, we find an ideal of self-overcoming, a figure who reclaims strength through an instinctive awareness of humanity’s inherited drives—yet, crucially, transcends their limitations. To rise above merely human impulses, the Übermensch does not simply climb out of the creaturely, the “ape” within. Instead, this figure integrates it, recognizing that instinct is not to be suppressed nor denied but understood as part of human architecture, a structural paradox to be understood and leveraged.

Berry’s insight—that the ape within denies before it acknowledges—strikes at the Übermensch’s struggle. Denial of our own basic nature often appears as a refinement, a moral virtue, and perhaps it is—but only in appearance. This denial becomes, in fact, an ape-like response, clinging to an illusion of purity by shutting out the troublesome recognition of its origins. And in doing so, it subverts the very virtue it seeks. That is, man’s denial of his base impulses does not uplift him; it enslaves him to a delusion of otherness. He imagines himself free from instinct when, in truth, he is caught in its most animalistic mechanism: fear of what is inseparably his own.

The ape in man, therefore, is not the animal instinct itself but rather its denial—a refusal to engage honestly with primal elements as if, through pretended distance, he could render them null. What the Übermensch represents instead is this engagement in earnest: a complete acceptance, even reverence, of what it means to be human and an insistence on owning all facets of this inheritance without self-deception. To transcend does not mean to rise above but to inhabit fully, seeing the whole and acting from a place of clear sight, beyond the quagmire of denial.

This refusal to face oneself is the crux of modern virtue: it’s less a striving for purity than it is a recoil, an instinctual act of recoil masquerading as enlightenment. And so, we must question, as Nietzsche does, whether moral striving becomes a feeble thing when it’s propped upon denial rather than self-possession. The Übermensch, in contrast, walks freely in his ape-like origins without denial, integrating the forces that shape his will. His transcendence is not moral escapism but a direct confrontation with inherited drives. Thus, the noble, aspiring “higher man” is not who dismisses the ape, but the one who faces it.

Through this lens, the mechanics of virtue are no longer about denial but about recognition: a command over self that is no longer ashamed to live fully within its architecture, acknowledging and owning the creature it must be to shape the human it chooses to become.